The traditional role of the database in scholarship has been as a repository – a place to store information for later retrieval. Over the past couple of years, however, I’ve found myself becoming more interested in the methodological use of the database not simply to store information, but to clarify points of tension between the questions we’re asking and the information we’re using to attempt to find answers.

My scholarship attempts to reassess medieval and early Tudor texts by setting paratextual and contextual elements equal with the text in examining questions of staging and hagiography. I do this for a couple of reasons: first, I think that our disciplinary and sub-disciplinary silos tend to get in the way of understanding how literary, devotional, and performed texts would have functioned as a part of the larger culture of late medieval England. Second, accepting that context requires us to not just examine the text as a platonic ideal, but also the means of its production, reception, and dissemination. In short, I treat the medieval text as part of a holistic. This work involves thinking not only of the ways that the text doesn’t fit our general expectations (performance and non-codex witnesses, for example, do not fit neatly into the categories we’ve created to deal with the codex book online), but also about the inscription, reception, and re-inscription of ideas.

As an aid to my thinking I’ve shamelessly stolen the idea of the network, taken from John Law’s explanation of Actor-Network Theory and applied to the written or performed text. Law describes ANT as

a ruthless application of semiotics. It tells that entities take their form and acquire their attributes as a result of their relations with other entities. In this scheme of things entities have no inherent qualities: essentialist divisions are thrown on the bonfire of the dualisms. […] it is not, in this semiotic world-view, that there are no divisions. It is rather that such division or distinctions are understood as effects or outcomes. They are not given in the order of things.[1]

Beginning with this viewpoint may seem counter-intuitive when talking about the use of a database as a methodology. After all, as Law notes, under ANT there are no inherent qualities or essential divisions, yet the process of rendering the analogue digital is fundamentally a process of reducing something to its most essential properties – at the most essential, the 0 and 1 or true and false of binary – and then presenting those as representative of the whole. For example, an algorithm is trusted to do the work of stripping out non-essential information from a song, reducing the audio waveform from a series of curves to a series of steps.[2] This aspect of the digital, however, is what actually makes a database useful as a tool for thinking through texts as part of larger questions regarding medieval culture.

One aspect of Actor-Network Theory that’s often talked about is the idea of the “black box,” a term that should be familiar to technologists as well. A black box is basically anything that takes in input and generates output, but doesn’t allow the observer to discern its underlying workings. In terms of ANT, a black box is an attempt to simplify a complex relationship for the sake of making the understanding of relations something that is manageable by the average person. We don’t really think about all the things that go into what makes our televisions, automobiles, and air conditioners work, for example. They simply do what we expect them to do when we turn them on – provide the input – and give us the expected results. Or, as Law puts it, “if a network acts as a single block, then it disappears, to be replaced by the action itself and the seemingly simple author of that action. At the same time, the way in which the effect is generated is also effaced: for the time being it is neither visible, nor relevant.”[3]

What happens, though, when your air conditioner breaks down, you try to watch television and the back of the unit sparks, or your car won’t start? Suddenly, that black box no longer functions as a single discrete unit, but instead has been reduced to the number of moving parts that actually made it up and which we’d conveniently ignored in an attempt to simply our lives. In attempting to solve the problem, we’re forced to acknowledge the pieces that make up the seemingly singular unit, their relationships, and the ways in which that relationship produced the effect that no longer works. The top has been removed from the black box and we can see how the sausage is made.

If the black box is thought of as an analog process, then the removal of the top of the black box and the examination of all the moving pieces can be seen as akin to the process of digitization. You no longer can simply elide everything together and make assumptions based on the item of your study as a single unit. Instead, everything has to be categorized, considered, and put in its proper place to determine what went wrong and to repair the whole. The relationship between these pieces – something that was assumed before – becomes of paramount importance. And it is in dealing with relationships that a database can excel.

Much like the process of creating an edition, reading a text or texts with the intent of inputting their relationships into a database forces you to think about them in a way that you may not have considered before. For example, when I was trying to understand the staging of the fifteenth-century Digby Mary Magdalene play, I created a database to record every location and character that are described in the manuscript. Where even with careful close reading I might have been content to accept that certain locations in the play are references by characters and don’t really exist, the fact that I had to concretely record that a character visited a particular location forced me to recognize how the various locations related to each other and to consider not just that certain locations exist or don’t exist in performance, but why they have to exist or not and what the implications of those relationships were on the overall narrative of the play, the heterodox way it presents the legendary material from the Magdalene’s vita, and to the likelihood that it was performed. This recognition of that interplay was then read back onto the larger cultural context of fifteenth-century East Anglia and the Magdalene cult in order to determine not just what is required to be represented in performance, but the reasons why certain assumptions regarding location in prior scholarship could not be valid.

Nowhere in this process was my intent to simply create a tool; that is an approach to using databases that I have seen in other scholarship and have followed myself as circumstances warrant. The list of manuscript witnesses on my Lydgate archive project and the force-directed graph attached to them are generated by a database that serves primarily as a tool for automating the process of keeping track of where manuscripts are in the transcription/display process, for example. There, the database simply exists to speed up a process that I could do manually and to serve a record-keeping function. It’s basically transactional. With the database for the Digby staging piece – and the work on East Anglian wills I’m undergoing in preparation for another piece – the database existed entirely to help me think through the various relationships (between characters and locations, or between testators and their beneficiaries), rather than to simply record things as they currently stand. Likewise, while the database for the Lydgate archive was created with a particular output in mind the staging database was not originally intended to have an output beyond simply being a way for me to reference connections in the play as I thought through the staging problem. The subsequent “output” that has been created – a visualization of where characters are at particular points in the play – was thus not the original end goal and was instead created as a type of quick shorthand for myself. That’s not to say that the database is static. The database has been further expanded to include the characters and locations for the Castle of Perseverance, and my hope is to include other place-and-scaffold works as time permits.

Obviously, as a methodological tool a database is not a Swiss army knife. It shouldn’t be considered to be something you can use for every single aspect of examining a text. What it does do, however, is not allow ambiguity. This means that the decisions you make have to be documented (if nowhere else than in your own notes), but it also means that points of tension are revealed that might have otherwise been overlooked. Those points of tension, in turn, can yield interesting results upon further examination. In that way, despite it not involving “making” qua “making” it does serve the same purpose methodologically as Critical Making does with physical computing. It uses digital tools – in this case, the database itself – as a tool for critical thinking about a problem, and as a method helps to complicate notions of data as objective or agnostic. In this way it serves not only as a tool to further the study of texts, but to interrogate and understand the underlying data structures that are classifying so much of our daily lives.

[1] John Law, “After ANT: complexity, naming, and topology” in Actor Network Theory and after. John Law and John Hassard, eds. Blackwell, 1999. 3.

[2] In fact, this reduction has occurred at least twice in most digital audio files – the initial recording has been rendered digitally, and then that format has been further altered through transferring the file into different formats, some of which are further compressed so as to make the file size smaller.

[3] “Notes on the Theory of the Actor-Network: Ordering, Strategy and Heterogeneity,” Systems Practice 5 (1992): 385.

Dr. Matthew Evan Davis currently serves as a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Lewis and Ruth Sherman Centre for Digital Scholarship at McMaster University. Prior to this he was a Lindsey Young Visiting Faculty Fellow at the University of Tennessee‘s Marco Institute and served as the Council for Library and Information Resources/Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow in Data Curation for Medieval Studies at North Carolina State University. His scholarly work deals primarily with late medieval English drama, hagiography, and material textuality, and his interest in digital scholarship comes in two flavors: first, he’s acutely interested in the “thingness” of digital presentation. Beyond that, though, he’s also interested in ways that digital tools and methods serve as shadow theories, influencing scholarship without being overtly recognized as doing so. The practical application of these interests can be seen both in his standard publications (most recently in Theatre Notebook and the Journal of Medieval Religious Cultures) and in his visualization (here and here) and 3D modeling projects. He is also developing (slowly) an online archive of the minor works of the poet John Lydgate.

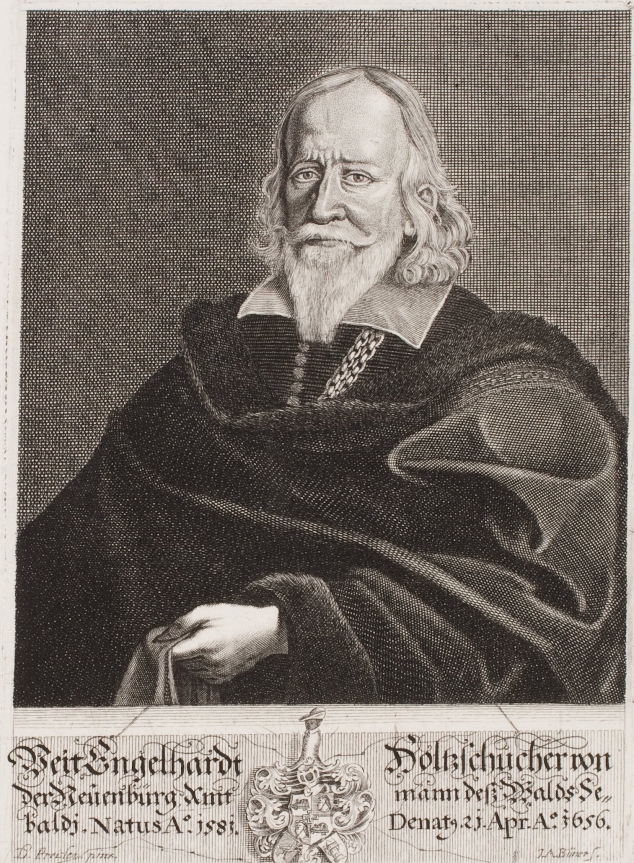

Detail of fol. 2r of LJS 445.

Detail of fol. 2r of LJS 445.

You must be logged in to post a comment.